In 1970, the Rothschild family took a strategic choice to break from their traditional banking operation and form their own investment trust company. Many questioned the decision at the time, wondering if leaving the banking system meant giving up access to resources and stability. However, history has shown that this was a foresighted decision. Fifty years later, the firm has grown into one of Europe’s most successful independent wealth management companies, managing approximately $4 billion in assets.

This story highlights an essential question: why is a bank not always the best option for rich families looking for complete asset management, even if it has a great brand and financial stability?

Consider this hypothetical scenario: after years of professional achievement, a Toronto-based physician has amassed $10 million in investable assets. The individual seeks a long-term, bespoke wealth management strategy for the family and contacts the private banking section of a large Canadian bank. During the initial engagement, the recommendation is a normal “balanced fund” portfolio. When the customer displays an interest in investing in new countries, healthcare industries, or optimizing tax structures, it is evident that such services may necessitate cross-departmental collaboration and additional permissions. Instead of obtaining an integrated experience, the client receives fragmented service delivery.

Such circumstances are not unusual in North American financial systems. They reflect how different institutions define and deliver wealth management. Core operations in the banking model are primarily focused on deposit gathering and lending. Wealth management services are frequently positioned as supplementary items that support larger client relationships or cross-selling goals. Institutional structure and regulatory constraints influence resource allocation, product development, and decision-making processes.

In contrast, the Rothschild family’s investment trust organization took a quite different approach. To increase transparency and preserve client cash, the corporation put assets with third-party custodians, separating asset management and custody functions. When the broader markets had not yet reacted, the firm dedicated a major amount of its assets to physical gold and energy investments—a strategy that proved resilient in the face of turbulence. Without the pressure of quarterly earnings reporting, the company could concentrate on long-term investment strategies.

A comparable change occurred across the Atlantic. As the Rockefellers built one of the biggest fortunes in American history, their focus moved from capital accumulation to capital preservation and succession planning. This resulted in the formation of Rockefeller Capital Management, a professional platform dedicated to serving complex family demands. The firm’s dedicated family office structure isolates wealth management from day-to-day banking, allowing it to focus on multigenerational planning, tax structuring, investment oversight, charity, and governance.

The Rockefeller family, now in its sixth generation, has not only conserved money but also established a structured governance system and passed down principles through generations. The story demonstrates an important point: genuine wealth management is a long-term, interdisciplinary endeavour that goes much beyond traditional financial services.

Institutional structure and risk control systems are also important factors in wealth management. While huge banks are widely regarded as secure, the custody models used by independent wealth management organizations provide a distinct type of protection. Client assets are often maintained by specialized custodians like as Northern Trust and BNY Mellon, which manage over $15 trillion and $47 trillion in assets, respectively—far exceeding the total asset base of Canada’s five largest banks. These custodians specialize in segregated account structures, stringent audits, sophisticated risk management systems, and client data security.

More crucially, the assets kept inside this framework are legally independent from the wealth management firm’s balance sheet. In Canada, this is known as “bankruptcy remote” custody. If the management business runs into financial difficulties, client assets remain safe and accessible. This is analogous to placing costly jewellery in a bank vault: regardless of the jeweler’s status, the goods stay unharmed.

In contrast, some bank-affiliated investment accounts may appear on the institution’s balance sheet. Though systemic failures in major banks are uncommon, in extreme instances such as insolvency or reorganization, client assets may be temporarily frozen or restricted in liquidity availability. The Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC) protects deposits up to $100,000, however this coverage is limited for high-net-worth individuals. In contrast, client assets held by independent firms can be quickly shifted to other managers with little disturbance or administrative burden.

Regulatory oversight also varies across models. Independent wealth firms in Canada are directly governed by the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization (CIRO), which enforces investment firm-specific compliance and professional requirements. This includes regular asset assessments, adviser certification, and ongoing education requirements. To preserve their licensing status, advisors must have recognized credentials like as CFA or CFP and complete quarterly updates.

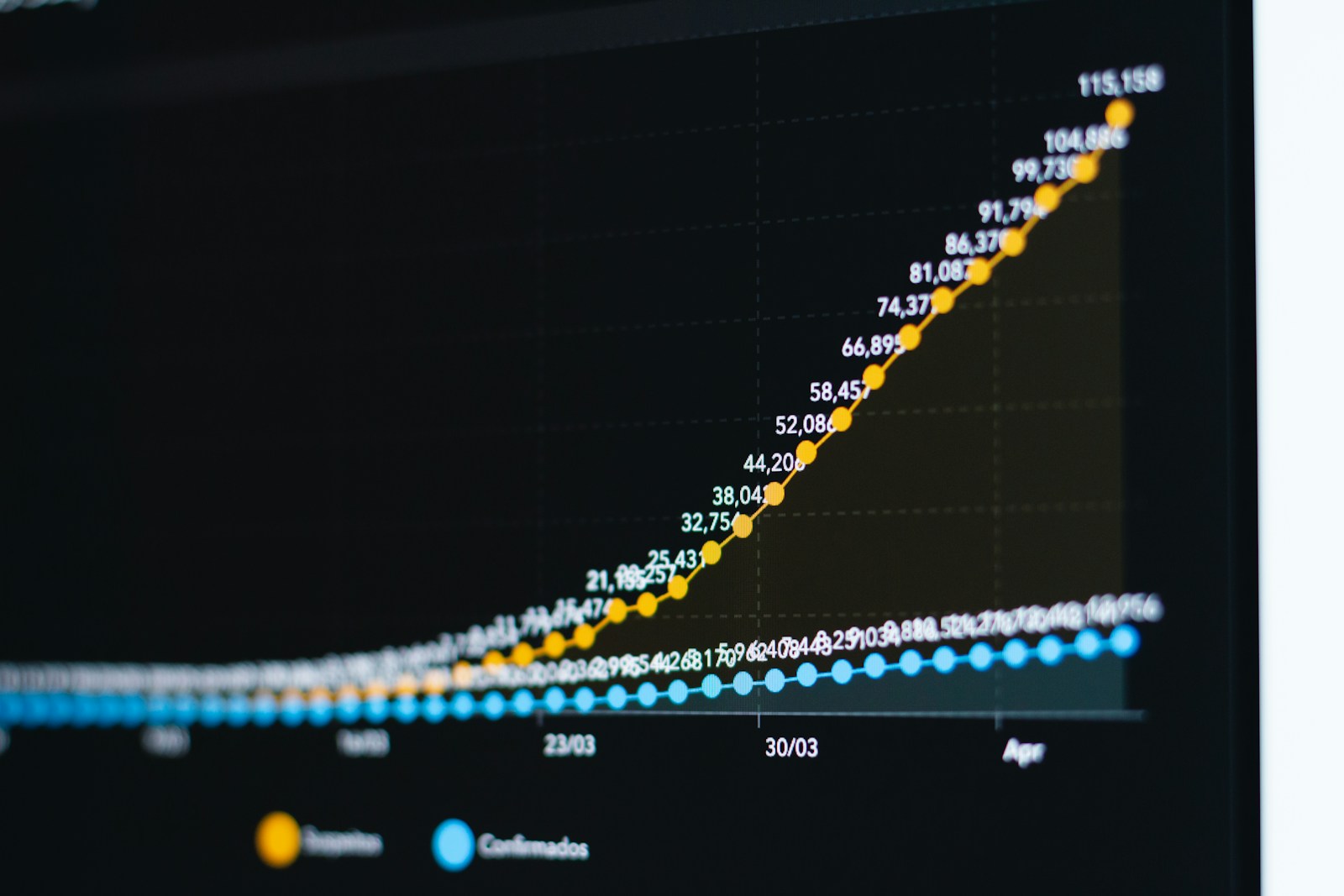

Differences in professional response tactics emerged amid the market instability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some banks took a conservative approach, encouraging consumers to maintain the course. Others, with in-house research teams, used the chance to adjust portfolios, increasing exposure to healthcare, technology, and growth sectors. This adaptability resulted in important consequences for some customers, demonstrating the necessity of active portfolio management during times of uncertainty.

Another major distinction is service integration. Independent wealth management firms frequently employ a diverse group of professionals, including financial analysts, tax consultants, accountants, lawyers, and insurance specialists. Working together, they provide cohesive plans for investment, tax, estate, and philanthropic planning.

Consider the example of a Toronto entrepreneur with a $0.5 million annual revenue. With a marginal tax rate of more than 53%, a well-structured plan that includes family trusts, income splitting, and capital gains optimization might lower effective tax rates to approximately 35%, saving nearly $1 million per year. Such complex tax methods necessitate interdisciplinary skills and are often unavailable through standardized product-based systems.

Independent firms can assist with estate planning by designing multi-generational wealth structures such as family charters, discretionary trusts, and tax-efficient intergenerational transfers. They can help with philanthropic planning by establishing private foundations, donor-advised funds, and legacy schemes that reflect both personal beliefs and tax efficiency.

Perhaps most importantly, independent investment managers provide consistency and long-term partnerships. These firms serve as counsellors, collaborators, and custodians of family capital on issues such as business exits, retirement, immigration, and second-generation schooling, as well as marriage, charitable giving, and crisis management. Investment portfolios are examined on a regular basis and altered to reflect life events and evolving goals.

This full-service model represents the transition of wealth management from a product-driven industry to a comprehensive family-office relationship. The capacity to give deep, integrated, and long-term support has become one of the key reasons why high-net-worth families are increasingly turning to independent firms—not only for profits, but also for structure, resilience, and long-term clarity.