When people talk about the risk-free rate, many naturally assume it’s the government’s credit rate — something entirely free of risk. In reality, that’s not quite true. This short piece takes a more technical angle, intended for readers who already have meaningful careers and assets, to provide a clearer framework for thinking about asset allocation.

The risk-free rate, by definition, represents the nominal return an investor can earn over time without taking any risk. Government bonds are commonly used as the benchmark to measure the risk-free rate across different maturities.

The credit spread refers to the excess yield corporate bonds offer over the risk-free rate, compensating investors for risks such as default. In 2025, credit spreads — both in North American investment-grade and high-yield markets — are near historic lows.

Several factors support such tight spreads. First, corporate coverage ratios, particularly debt relative to EBITDA, remain at healthy levels. Second, the overall quality of issuers has improved over time. Third, post-pandemic bankruptcy rates have dropped significantly. Moreover, just as equity investors tend to “buy the dip,” credit managers often step in when spreads widen. There’s no shortage of buyers in the market.

Yet few realize that even U.S. government bond yields aren’t entirely risk-free. The risk premium embedded in Treasuries doesn’t stem from inflation expectations or short-term rate outlooks, but rather from concerns about sovereign default risk. As early as the 1990s, politician Ross Perot warned that the U.S. was on an unsustainable fiscal path — when total debt was only $4 trillion. Thirty years later, that figure has surged past $37 trillion.

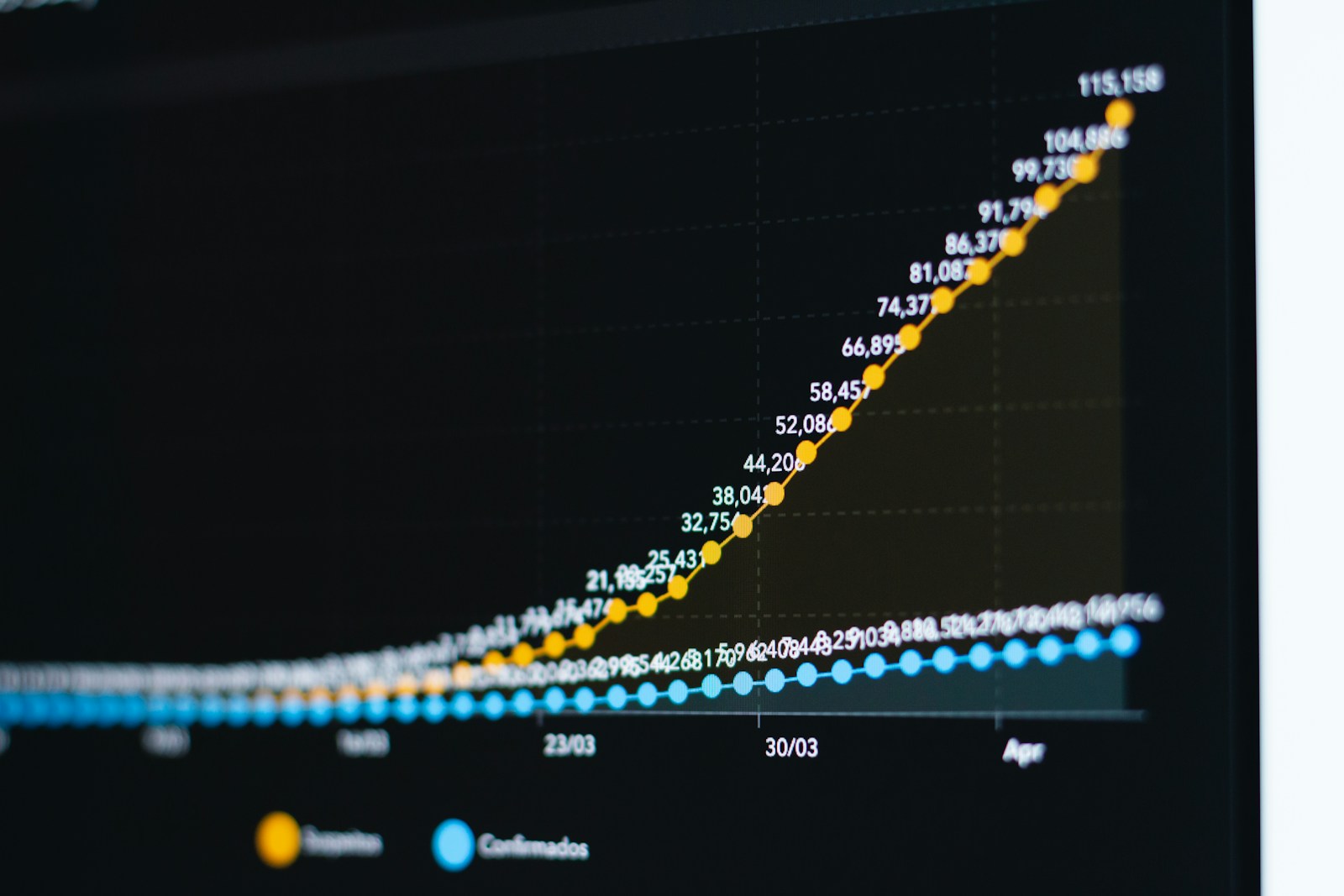

The existence of U.S. Treasury credit default swaps (CDS) itself proves that government yields are not completely risk-free. If they truly were, there would be no need for hedging instruments. CDS pricing reflects two key points:

-

Treasury yields now include a measurable risk premium;

-

That risk increases with maturity.

Data from 2019 to 2025 show that both 1-year and 10-year U.S. Treasury CDS spreads are clearly above zero — with 10-year levels significantly higher, indicating the accumulation of long-term risk. This pattern spiked during the 2020 pandemic and, though it later eased, has remained historically elevated.

For example, if Apple’s 10-year bond spread over the 10-year U.S. Treasury is 30 basis points, but the Treasury itself carries roughly 10 basis points of risk premium, the true spread above a genuinely risk-free rate is closer to 40 basis points.

For high-net-worth investors holding U.S. Treasuries and credit exposure, it’s important not to take the “risk-free rate” at face value. Historically low credit spreads may conceal hidden risks. The ultimate credit risk premium might be understated by traditional measures.

In short, the risk-free rate remains a useful benchmark — but thoughtful asset allocation requires recognizing its limitations and ensuring genuine diversification across risk sources.