If you look closely at the patterns of global migration around the world in recent years, you’ll see a trend: people and businesses are always moving to places that offer more economic freedom and efficiency. North America is the best example of this:

The California Gold Rush of the 1800s brought in tens of thousands of immigrants who left their homes behind. They weren’t just after gold; they were also looking for economic freedom and opportunity. They were leaving the East Coast because it was stagnant and inflexible.

In 2010, basketball player LeBron James took a wage cut to join the Miami Heat. He thought about the team’s strength and the fact that Florida has no state income tax, which was like a “raise.” The Heat wasn’t the ideal pick for his reputation, but it made a lot of sense from a financial and lifestyle point of view.

A lot of Fortune 500 firms and their CEOs are moving today to cut down on taxes and costs of doing business. In 2021, Elon Musk transferred Tesla’s headquarters from California to Austin because he liked how cheap things were there. In 2020, Oracle Chairman Larry Ellison moved to Texas, where he saved millions in taxes while looking for a better business environment and more talented workers. These CEOs are not only saving money for shareholders, but they are also giving employees more money and a better quality of life. This is the new “economic gold.”

But what do these examples have to do with wealthy families in North America? The answer is that they can find and take part in the capital development and operational opportunities that come up during this migration “process,” instead of moving and buying property themselves and then having to deal with the risks of “results” that come from things like climate and environmental conditions that aren’t always clear.

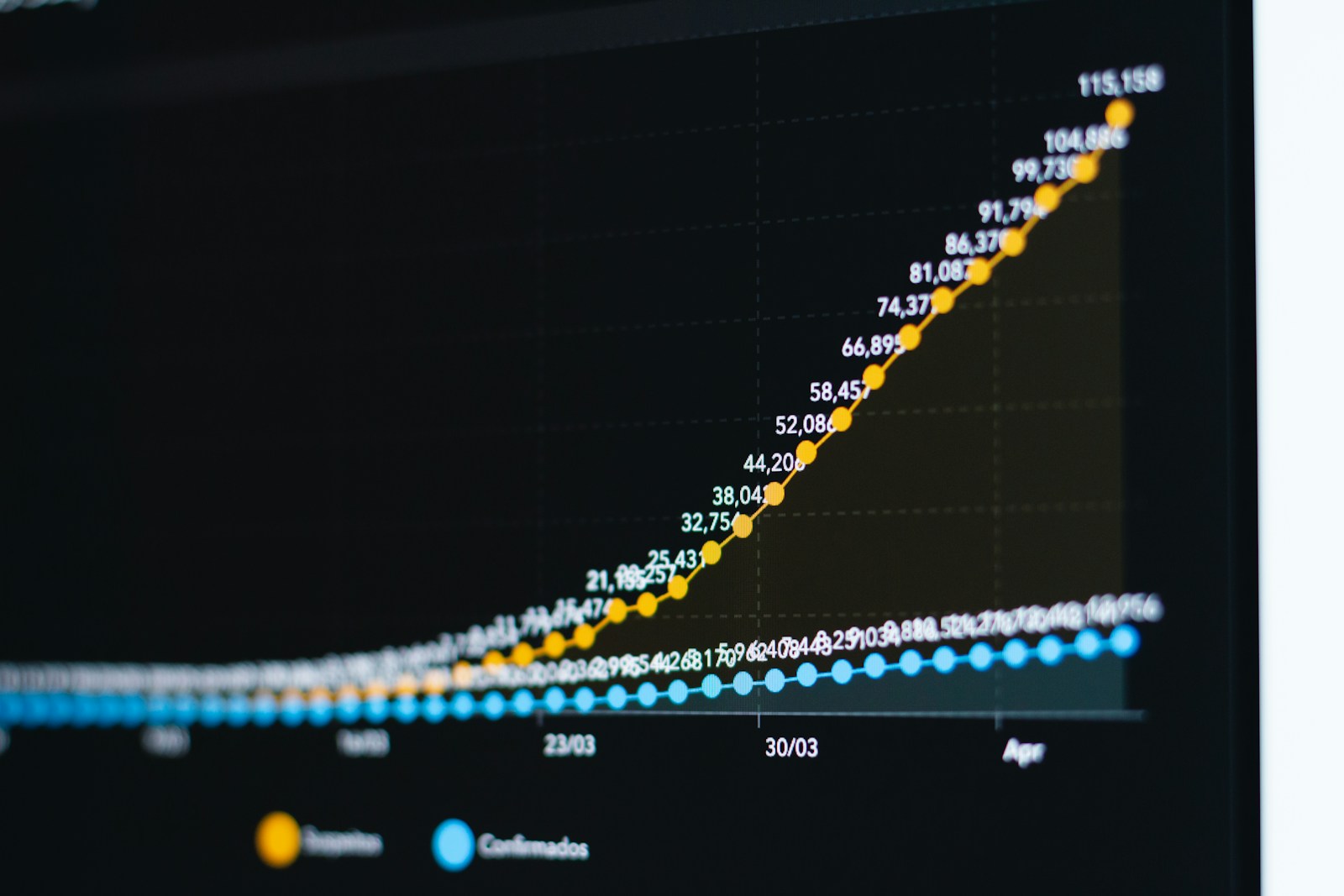

If you look closely at the Federal Reserve’s data, you’ll see that the energy, financial services, and construction industries grew the most in 2024. These were the key businesses that benefited from companies moving to other states. Tesla’s Gigafactory and Oracle’s large-scale personnel relocations produced a whole ecosystem: construction companies built new buildings, banks handled new business, and energy providers made sure there was enough power. With the Texas governor in charge, more than 2.5 million new employment created a cycle of people moving in and demand for housing and services.

This structural migration isn’t simply numbers or arrows on a map; it’s important for every investor since it helps them decide how to allocate their own assets.

When businesses and people move to Texas, Florida, North Carolina, and other places, the first effect is on the middle class’s need for “affordable” housing. There may be too many luxury apartments in downtown locations, or the number of vacant apartments may be rising. On the other hand, there aren’t enough multi-family homes in suburban areas with strong schools. New rental projects that have stable rental income growth and occupancy rates are good for developers. As more and more people move in, these places, while not fancy, are where the next wave of wealth transfer will really begin.

High-net-worth families and investors can act as “capitalists” in developer project portfolios that let capital grow steadily. This is similar to what happened to people after the 2009 financial crisis, when they took advantage of future markets with stable, secure returns and got in early on assets with supply-demand mismatches, becoming “capitalists who reap the rewards.”

The systematic risk level of these asset management techniques is just around half that of North America’s “S&P 500” index. However, during the past 30 years, their average annualized returns have always and steadily been higher than the S&P index. There has never been a year in the entire history that had negative annualized returns, and volatility has been very consistent.

A lot of people easily connect these kinds of techniques with real estate price trends because they think that prices need to go up for them to make money. In fact, it’s the opposite: they don’t depend on local asset price increases; instead, they focus on getting a share of genuine company earnings. So, as house prices go down, there may be more and better chances to invest. In other words, it doesn’t care about “how much the house is worth,” but rather “whether the underlying asset portfolio that creates cash flow is healthy and sustainable enough.”

Warren Buffett once said something that a lot of people heard: “Risk comes from not knowing what you’re doing.” Investors who really know how debt-type instruments work don’t have to worry about the “blowup” dangers that the general public does.

“Debt-type” products in China are different from the usual “equity-type” products since they are based on contractual rights that make it clear who gets paid first and who gets the equity. Even if projects fail and firms go through bankruptcy reorganization, investors as creditors still have priority protection in liquidation and can often get all of their principal back, with no effect on their investment portfolios.

Of course, these kinds of instruments aren’t meant for “betting,” and they shouldn’t be the main way to decide how to allocate assets. For families with a lot of money, a better way to employ these private placements is as a modest component of their overall allocation, where they can provide relatively predictable returns or protect against interest rate risk in the asset structure.

The instruments themselves don’t cause real risk; it’s typically the wrong way of comprehending and allocating them that does.

High-net-worth families and “old money” in North America have known for a long time how to find price-value dislocations in structural shifts through professional channels. If you can also use these dislocations to your advantage, what you see won’t just be a way for people to move, but the main way you will make money over the next ten years.