Real estate investing is one of the clearest expressions of cognitive bias in wealth allocation.

For many Chinese investors, once capital is transferred from China into North American accounts, the first instinct is often the same: continuous property acquisition. Portfolios quickly become dominated by residential and rental properties far beyond personal living needs.

Daily attention is focused on housing price trends, mortgage policy incentives, interest-rate spreads, and banking leverage conditions that push prices higher. Much less attention is given to more fundamental investment variables: rental yield sustainability, vacancy risk, liquidity constraints, and the true all-in cost of ownership.

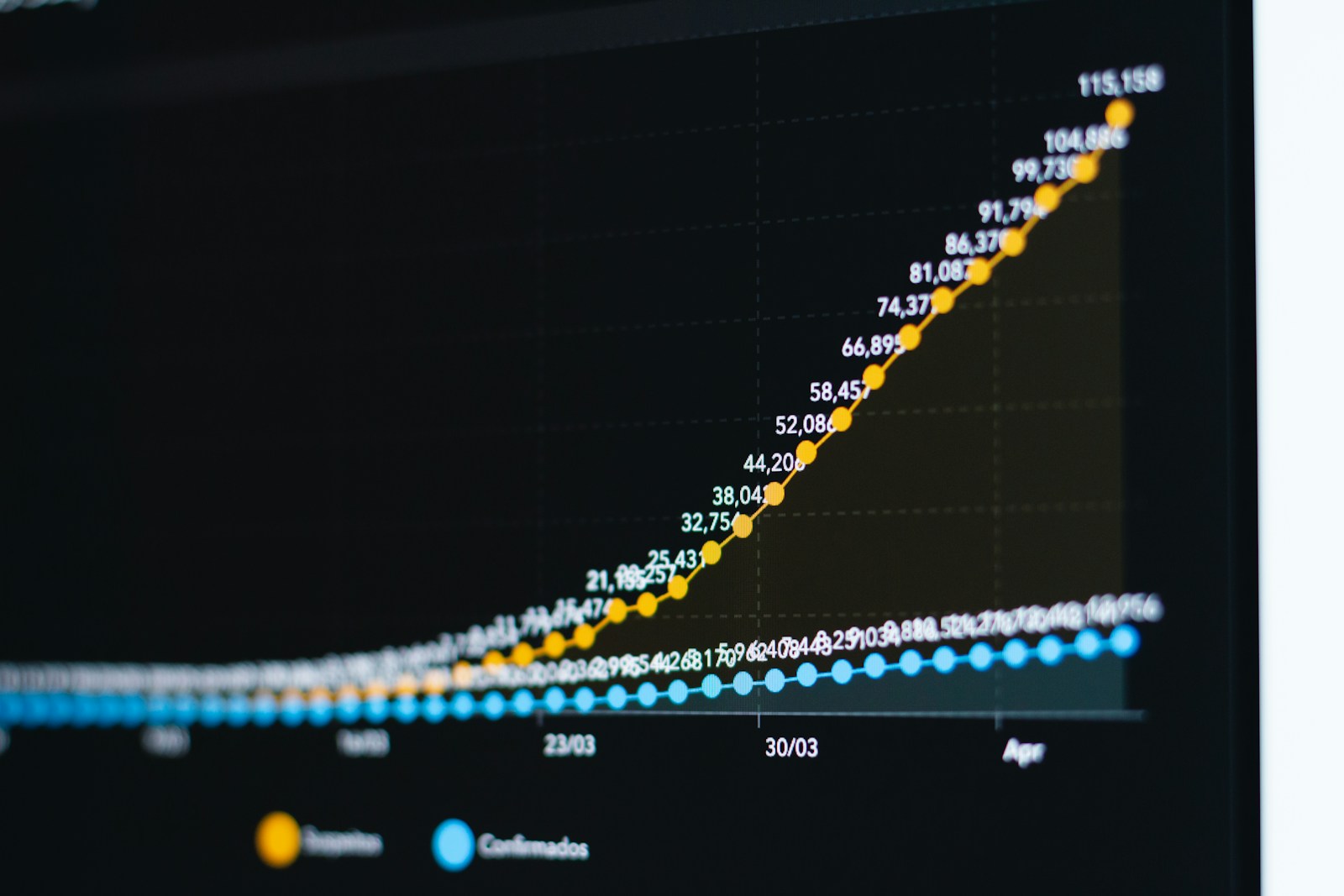

From a performance perspective, this strategy has appeared highly successful over the past decade. A property purchased for $1 million in 2015 may now be worth over $2 million in 2025. Assuming annual rental income of $40,000, the nominal return approaches 10% per year, outperforming many equity portfolios. With 3–4x mortgage leverage, the theoretical capital efficiency can appear even higher, sometimes projected at 12–14% annually.

However, behind these attractive figures lie several structurally underestimated risks.

First is liquidity risk.

For individuals, 99% of the time life runs normally — but in the 1% of scenarios where urgent capital is required, the need for liquidity is absolute. Real estate is structurally illiquid by nature. In emergency situations, investors are often forced to accept significant discounts to fair market value. After transaction costs — broker fees, legal fees, taxes, and closing costs — the effective loss can easily exceed 20% of asset value. When wealth is concentrated in property, liquidity stress becomes systemic risk at the household level.

Second is concentration risk.

This is the most underestimated and potentially most destructive risk. Investors naturally concentrate capital in assets they understand and have previously profited from — often in a single asset class, a single city, or even a single neighborhood. This is not diversification; it is geographic and structural concentration. When economic conditions, policy environments, or regional demand dynamics shift, the impact can be devastating.

During the pandemic, rental demand collapsed across many North American cities. Strategies dependent on short-term rental platforms such as Airbnb faced mass insolvencies as tourism stopped and regulatory pressure increased.

Third is leverage risk.

Across financial history, asset quality has always mattered more than leverage. Excessive debt is fundamentally a high-risk strategy used when capital scale is limited. A well-constructed diversified portfolio can achieve 10–15% annualized returns without structural leverage, with far greater stability and predictability. High leverage transfers control of your financial destiny to macro policy cycles — especially central bank interest-rate decisions — amplifying volatility and systemic vulnerability.

Finally, there is cyclical risk — one of the most severe structural limitations of real estate.

Property markets are inherently cyclical, capital-intensive, slow to adjust, and highly sensitive to credit conditions. Unlike liquid financial assets, real estate cannot be rebalanced dynamically. When cycles turn, capital becomes trapped. Valuations adjust slowly, liquidity evaporates quickly, and recovery periods are long. This creates long duration drawdowns with limited tactical flexibility for investors.