My work frequently brings me into close conversations with senior executives from major North American asset management firms—people like Ryan Dickey from Mackenzie or top fund managers from Fidelity such as Mark Schmehl and Will Danoff. Many of these seasoned investors have told me that each year, they send analyst teams to mainland China, hoping to capture a share of what they perceive as the country’s “future opportunity.” On the surface, the story makes sense: impressive headline numbers, world-leading GDP growth, the tail end of a cheap-labor advantage, and a rising middle class eager to spend. From a Western financial-modeling perspective, it looks flawless.

What most of them fail to grasp, however, is that there’s a deeper, unsolved problem that distorts their judgment: they don’t understand the role of culture and policy in China’s economic engine. Their grasp of Chinese behavioral logic is nearly zero. When they try to quantify China through a North American economic lens, their tools are precise—but they’re aimed in the wrong direction.

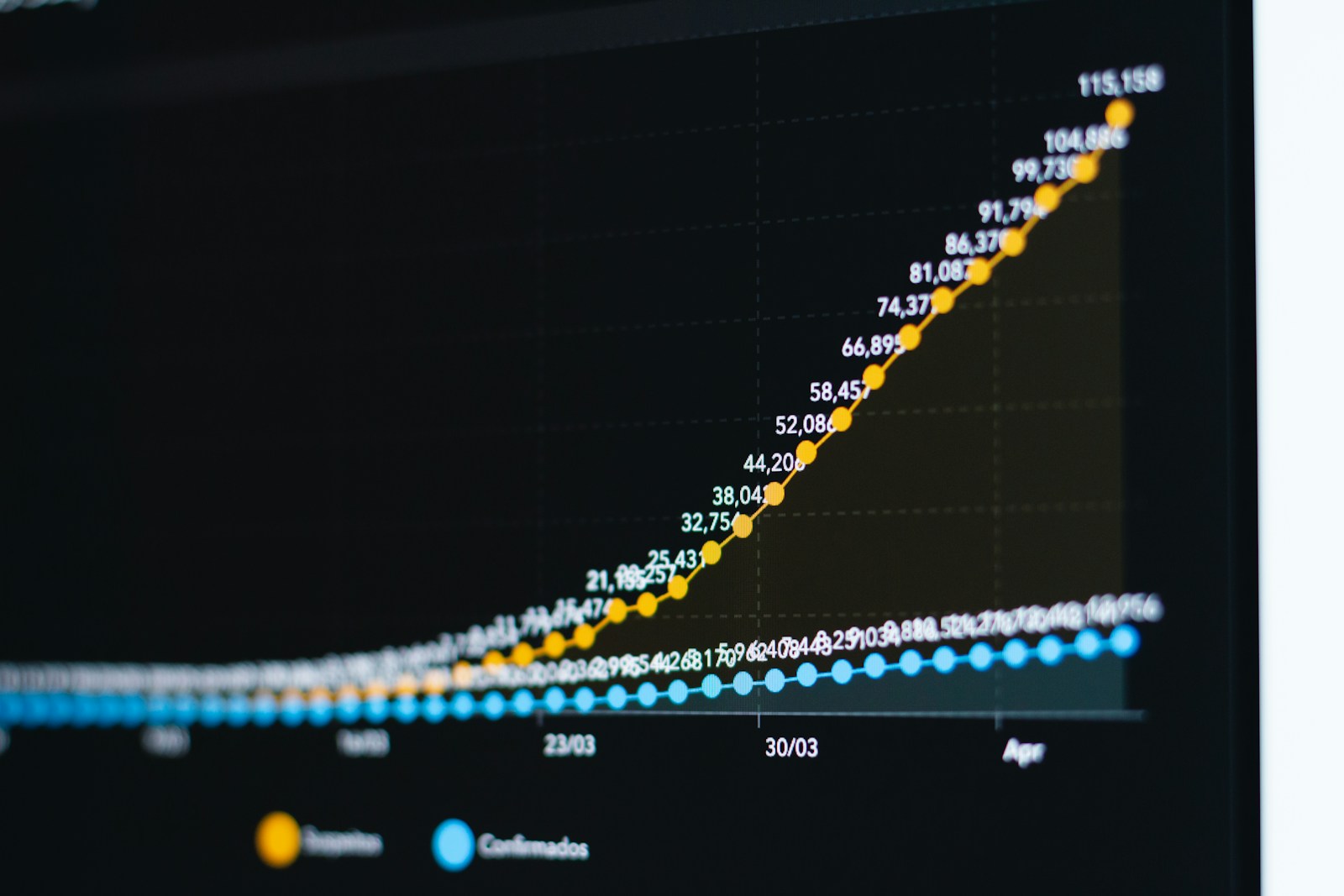

After the pandemic, China’s GDP growth did rebound respectably in 2023. But anyone who stops at the aggregate data will assume that the risks are gone and that the country is thriving again, just like the state media portrays. A closer look at the components tells a different story: shifts in consumer behavior and growing policy uncertainty have made this recovery far less sustainable than Western investors imagine.

North American analysts often summarize aging demographics with a simple formula: “Labor costs rise, manufacturing competitiveness falls, savings decline, and consumption expands.” In China, the equation plays out very differently. Because the country’s development was so rapid, its social structure never had time to mature. Aging is now accompanied by widening wealth inequality and social stratification—huge disparities in spending power across age and class. These structural imbalances carry long-term implications for the entire economy.

Any economy driven primarily by real-estate growth carries latent risk. Imagine if Canada’s housing contribution to GDP suddenly dropped as sharply as China’s did in recent years—many property-obsessed investors would panic. But mainstream North American investors might interpret that as a healthy sign of market liberalization, freeing up resources for more productive sectors. In China, however, due to its historical and institutional path, such a decline is not a correction but a deep economic crisis. Those who truly understand the trend have already stopped viewing Chinese property as a quality asset—and will never return to it.

New energy and technology are two other sectors heavily hyped by Western capital. Yes, China’s pace of innovation and industrial scale are remarkable. But dig deeper, and you’ll see competition so fierce that few outsiders can fathom it. Many companies’ so-called “technological advantages” boil down to larger screens or bigger batteries—growth fueled more by financing and market capture than by genuine innovation. Even though a few firms like Xiaomi have built strong ecosystems, the overall intensity of competition is eroding profitability. The bigger issue is China’s lightning-fast innovation cycle: in traditional industries, leadership might last years; in tech or new energy, it may last only months. Unless you can continuously stay ahead—which almost no one can—the market will hit you with the iron fist of reality.

Western analysts excel at processing information through logic, data, and models—that’s their strength. But in China, policy alignment and power dynamics are the real levers of success. No one can remain at the top indefinitely, because the market is fluid, policy-driven, relationship-driven, and centrally controlled, not purely rational or data-driven.

For global fund decision-makers and high-net-worth investors, the essential question isn’t “Is China’s economy strong or weak?” but rather: Can you dynamically navigate power, opportunity, and risk within such a distorted social structure? If not, investing there becomes less a matter of strategy and more a gamble of circumstance—and no amount of research reports or headline optimism can change that.